Self-examination: On Respect Life and ‘Oppenheimer’

“The Italian navigator has just landed in the New World.” That is reportedly the message sent to the head of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wartime National Defense Research Committee when the team of scientists, led by Enrico Fermi, succeeded in creating an atomic chain reaction at their secret facility at the University of Chicago. What was called the Manhattan Project was underway, and residences, laboratories, offices and sentry stations had sprung up in the nowhere-lands of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

“The Italian navigator has just landed in the New World.” That is reportedly the message sent to the head of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s wartime National Defense Research Committee when the team of scientists, led by Enrico Fermi, succeeded in creating an atomic chain reaction at their secret facility at the University of Chicago. What was called the Manhattan Project was underway, and residences, laboratories, offices and sentry stations had sprung up in the nowhere-lands of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

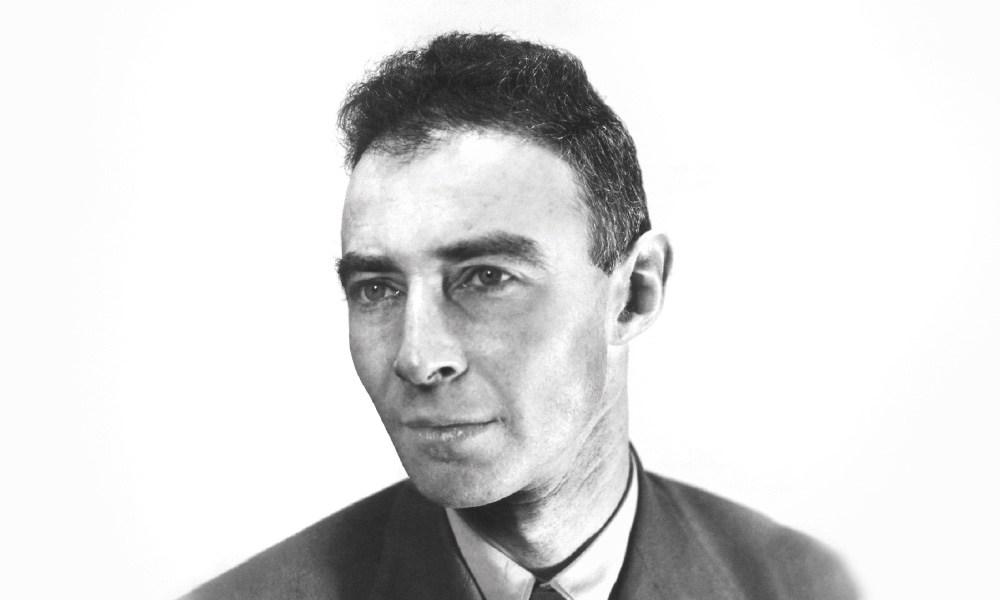

The result of this work was the obliteration of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Anyone who has seen the film “Oppenheimer” understands the discipline, anguish and moral ambiguity which participation in creating the atomic bomb entailed.

Benefits and burdens

During this Respect Life Month, it is important to acknowledge some of the blessings that the theories and discoveries of quantum physics and the nuclear age have brought. The development and use of transistors, lasers, electron microscopes, MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) and nuclear medicine have transformed communications, space science, plus medical diagnoses and treatments. Some would add the development of nuclear power plants as another blessing in reduction of reliance on fossil fuels. As we have seen at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima — and in ongoing concern about the fate of Zaporizhzhia in Ukraine — those power plants are both benefit and burden because of their risks.

Our moral reflection as Catholics has to question how the enrichment of U-235 and the production of The Bomb, its massive anti-population results, and the arms race that ensued, can be justified. On one hand, we can dismiss the question by saying that most who were involved in the atomic bomb’s production didn’t know what the larger project was. And clearly those who developed it with minimal understanding believed they were performing a patriotic duty to end World War II. On the other hand, those who did have a keener grasp of the massive power and potential effects of the bomb were engaged in putting theory into practice on orders or invitation of the government and muted the ethical questions. Then there are those whose ex post facto evaluation of the dropping of two anti-population bombs was pragmatic: it worked. The bombs saved American lives and Japan surrendered.

Saints, popes and Catholic teaching

But pragmatism — the argument that the end justifies the means — is not Catholic morality. With today’s awareness, we are duty-bound to challenge the development of weapons that target whole citizenries. We have to question not only such development but also their stockpiling and the ongoing threat of their use, whether we are talking about nuclear, biological, chemical or other weapons that disable and destroy indiscriminately.

Sts. John XXIII, Paul VI, John Paul II, plus Popes Benedict XVI and Francis, have repeatedly condemned war in general and anti-population armaments in particular. The Second Vatican Council denounced the frenzied arms race that followed World War II and noted that the fortunes spent on weaponry robbed the poor and left programs that benefit the common good — like food relief, education, health care, etc. — underfunded.

In The Challenge of Peace, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in their book-length pastoral letter (1983) enunciated criteria for a just war. Included in those criteria was attention to matters of justice and injustice, not only in the rationale for going to war (jus ad bellum) but also in the conduct of war (jus in bello). They observed that a war can be deemed unjust if the means used are disproportionate to the end intended (restoration of peace) — and also if those means target the defenseless.

The bishops also questioned the morality of continuing the research and development of such weapons (those of mass destruction). The common argument offered by proponents of such development is that holding these weapons is a form of deterrence: it makes an enemy less likely to use them. The counter argument, suggested in The Challenge of Peace, is that the possession of such weapons enhances the probability that sooner or later, by accident or intent, they will be used.

St. John Paul II’s encyclical Evangelium Vitae (The Gospel of Life, 1995) made the most strident condemnation of three moral evils. Speaking in union with and on behalf of the bishops of the world, and using the phrase “I solemnly declare,” the saint condemned abortion, euthanasia and the deliberate killing of innocents.

Popes Benedict XVI and Francis have reminded us in various ways that human beings are not disposable; it is immoral to write them off as collateral damage.

Respect Life Month

On Oct. 22 we recall three events. The first two are the feast day of St. John Paul II, a champion of life, and the day of his election in 1978 to a remarkable and world-changing papacy that lasted nearly 27 years. It is also the 61st anniversary of the announcement of the Cuban Missile Crisis. President John F. Kennedy spoke to the nation about the military and naval blockade in response to the Soviet Union’s transport and installation of missiles in Cuba. The crisis generated long-term dread that nuclear war was imminent — a World War III that, by then, would have employed many more megatons of fire power than the bombs dropped on Japan.

As the “Italian navigator” code phrase channeled to FDR suggested, we did indeed enter a new world with the successful accomplishment of chain reactions, nuclear fission and fusion and the development of atomic weapons. At the conclusion of “Oppenheimer,” the genius mathematician and physicist who directed the work at Los Alamos says to Albert Einstein, “We were afraid that we might destroy the world. I think we did.”

This month, as we consider the host of critical life issues — abortion, euthanasia, the killing of innocents and all the ways of devaluing human life — we are called to self-examination. We have to ask ourselves how we personally and collectively heed the moral compass that shows us how to counter a culture of death and truly build a culture of life. How do we prime ourselves and influence others to think, speak up, act and vote with genuine concern for human dignity — for each and all?

Our lives and the lives of others depend on it.

Sister Pamela Smith, SSCM, Ph.D., is the diocesan director of Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs. Email her at psmith@charlestondiocese.org.