Bishop England's first Fourth of July

The Diocese of Charleston was established on July 11, 1820. Rt. Rev. John England, the first bishop of the new Catholic community, was an immigrant to this great nation. The Irish-born native arrived in his new diocese on Dec. 30, 1820, with a bright vision for Catholics in this missionary frontier that stretched across three states. He sought to build a place for Catholics to live in harmony with the democratic experiment that was the fledgling American nation.

The Diocese of Charleston was established on July 11, 1820. Rt. Rev. John England, the first bishop of the new Catholic community, was an immigrant to this great nation. The Irish-born native arrived in his new diocese on Dec. 30, 1820, with a bright vision for Catholics in this missionary frontier that stretched across three states. He sought to build a place for Catholics to live in harmony with the democratic experiment that was the fledgling American nation.

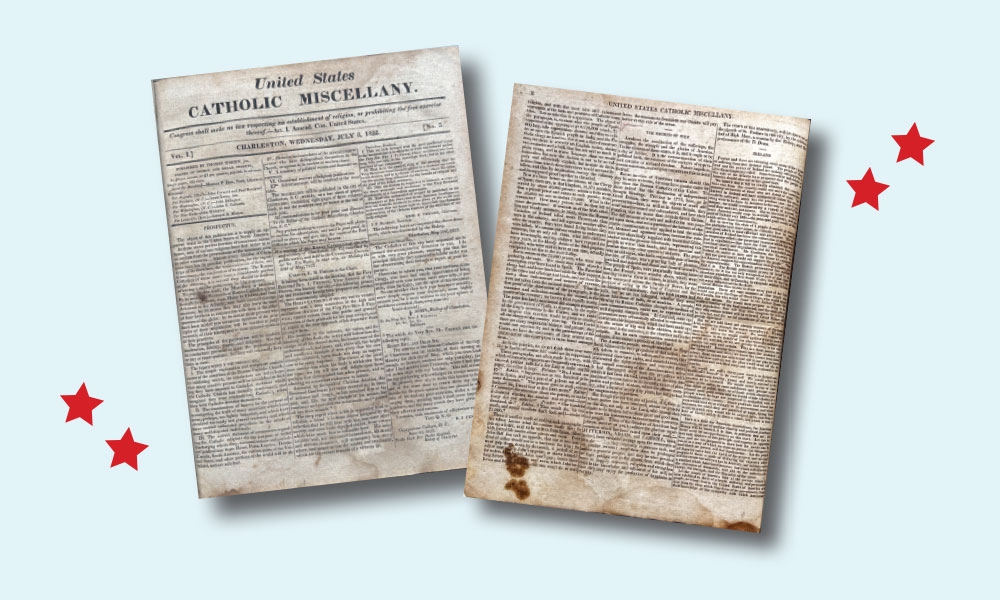

England’s position as bishop of the new Diocese of Charleston afforded him an accelerated path to citizenship, cutting the two-year naturalization process in half. The bishop celebrated his first Fourth of July as an American citizen with an article in the United States Catholic Miscellany, the first national Catholic newspaper, which he founded. Excerpted from that July 3, 1822, edition are his words:

“The Fourth of July awakens the recollection of the sufferings, the struggles, the triumph and the glories of America. To the citizens of these states, it is, and it ought to be, a day of Jubilee. It is the commemoration of their political birth, the evidence of the energies of oppressed votaries of national freedom. Nature impels to, reason sanctions, and religion consecrates this national festival.

“But to no class of American citizens should this day be more welcome, for none have greater cause for joy than the Roman Catholics of this Union. To them indeed has the Declaration of Independence brought blessings. Previous to 1776, here, as in Great Britain, they were the objects of scorn and persecution — here, as well as in Great Britain, they were misrepresented and

calumniated, and here their situation was far worse than even in Great Britain …“The American people, strongly attached to England, followed the very prejudices of that nation; until, driven to examine, to reflect, and to reason, they discovered their own rights, and asserted them, they discovered the rights of others and conceded them. The correct reasoning of the American mind, when it had disengaged itself from the prejudices with which it had been fettered, brought it at the very formation of its constitution to do instantly an act of plain justice and political wisdom …

“But though the act was one of justice, still, they, to whom justice has been rendered, should be grateful on this day, not only the Lord, who caused their claims to be broken, but to those great and good men, who were his instruments in emancipating a persecuted people.”

Bishop England came to the United States expecting to serve a population of Irish and French immigrants who were seeking acceptance in a land rife with misconceptions and prejudices. When he arrived, however, he found something unexpected: a significant population of enslaved people who were Catholic.

To those who are familiar with the Old Testament, we can see the bishop’s recognition of the plight of his enslaved flock. The day of jubilee which England uses as a model for the Fourth of July is a day of freedom for those fettered by social and physical chains. The jubilee was a day on which the slave was freed, the stranger was returned to his ancestral lands, the debtor had his ledgers cleared and the scattered family was reunited.

The new bishop of Charleston raised up the Fourth of July as a celebration of hope for a more perfect Union. England sought to bridge the social gaps between the impoverished Irish immigrants seeking religious toleration, the French refugees fleeing genocide in Haiti and the enslaved Catholics of western Africa who had been torn from their homelands. He saw this as possible only

through the elimination of prejudice.

England based his dream of Catholicism in America on personal encounter and open dialogue that was unfettered by ignorant persecution. All members of his new Diocese of Charleston, enslaved or free, rich or poor, were united through one faith in the hope for a freer tomorrow.

This July 4, our diocese continues to celebrate the independence of this nation in the same hope of a more perfect Union. The example and testimony of our first bishop calls us to reflect on what our hoped-for future will look like. Are our current views of our brothers and sisters in Christ chained by misconceptions, prejudices or ignorance? Do we allow ourselves to be divided by

influences outside the universal nature of our Catholic faith? Or do we, instead, follow the example of Jesus, of Bishop John England and of our new Pope Leo XIV in the effort to be more perfectly united as the people of God?

Let this Independence Day bring us closer together as a Catholic people and reaffirm our commitment to shape our country into a more perfect nation under God.

Benjamin Weiskircher is a Church history Ph.D. student studying at The Catholic University of America. He has researched the original United States Catholic Miscellany and the development of an American Catholic identity. Email him at ben.weiskircher@gmail.com.